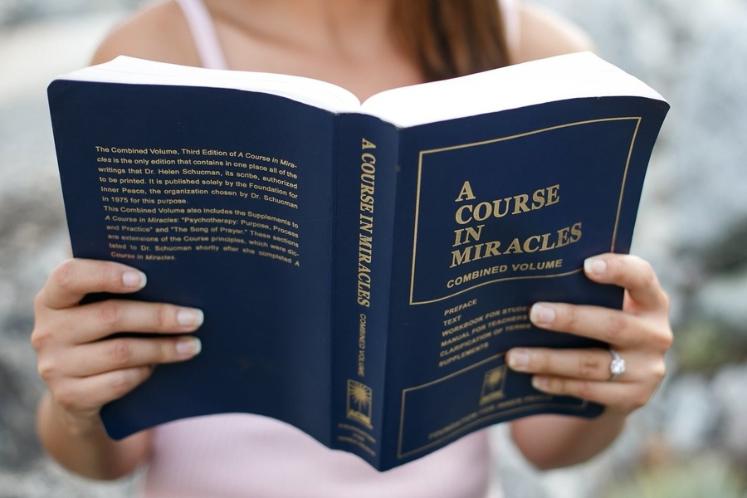

Before you start to seriously go out and buy a course in miracles, you need to learn some terminology and become familiar with book publishing and production process. For example, while most people think of book collecting only in terms of the final product as it appeared in the bookstore, there are other elements of a book that are more valuable, more elusive, and more heavily collected. Plus, the more you know about the history of books and how books are constructed, the more finely tuned your critical senses will be, and the more you’ll appreciate finding a truly good book. This article is an attempt to educate and provide you with resources to get you started in book collecting.

For the collector, there are three primary things to consider when buying a book: EDITION, CONDITION and SCARCITY in this condition and edition. Understanding these areas is the different between success and failure, between being able to build a collection of treasures and an assortment of reading copies, between being able to collect and sell for money, or just going out and buying a lot of worthless books.

The used and collectible book market divides into three neat categories:reading copy, antiquarian, and modern first edition. Are books you can take to the beach or into a bathtub. They’re the largest part of the book market, and they’re everywhere. If you buy a book with anything in mind other than collecting, you’re buying a reading copy.

Antiquarian book lovers seek out classic old volumes—editions of Scott, Wordsworth, the Bay Psalm Book, examples of fine printing and binding from centuries past. Modern first edition collectors tend to limit themselves to this century, to the writers who have defined the times we live in, such as Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Faulkner.

This is going to be your opening stock, so take a minute to appraise what you own. Do you have a lot of paperbacks with cracked spines and tattered covers? Or do you have a nice selection of good hardbacks neatly care for, books you brought as soon as they came out? The fact that you own books at all shows that you’re a lover of books, which is the first step to becoming a serious collector.

So, obviously, you’ve got to learn how to identify first editions to avoid making costly mistakes. After all, if you think it’s a first and you turn out to be wrong after paying a premium. The problem is, nearly every publisher has its own method of identified first editions. You can memorize the policies of every single publisher in the history of the book trade, and even then you’ll make mistakes, because all of the rules have exceptions. On my shelves, and on on the shelves of every collector I know, there are at least a few books that looked like a first of first, but turn out later to be plain old books instead.

As general rule, there are two things to look for right off the bat:a statement of edition, or a number line. The statement of edition is exactly that: on the copyright page, the book says “FIRST EDITION” or “SECOND EDITION” or FIFTY-THIRD EDITION.” Or if not “edition” it will say “printing”. With lots of publishers that’s all you’ll need to find. Unfortunately, some publishers don’t remove the edition slug from subsequent printings; or sometimes a book club edition will state that it’s a first; or sometimes there’s nothing stated at all.

The next thing to look for is the number line. This is a sequence of numbers which, on the first, usually go from 1 to 10 (some publishers will go 1 to 5 and then the five years around the year of publication: for example, 123459495969798); it may be in order, or it may start with 1 on the left, the 2 on the right, and so forth, with the 10 in the middle. Look for the 1. On every publisher employing a number line except Random House, a number line with a 1 is a first edition. Random House, just to be sure that no one can ever be sure, use a 2 on the number line and the “FIRST EDITION” slug.

There are some publishers who indicate a first edition by not indicating it. If you don’t see anything that says it’s a second or third edition, then it must be a first. There are other publisher who code the information into the book somewhere, but it isn’t always easy to find.

These little differences, about where the photographs should be, wrong lines printed in the book, etc., are known as points. The easiest way to start learning points is the obvious one: pay close attention to the better price guides, which rarely fail to list the major points. Never just look at the price, look at the entire entry. Because points are so vital, it’s time to introduce one of themes of this article: to collect successfully, it is important to specialize to a large extent. You are never going to learn the full field of points, of every single detail differing in every single book. In the comfort of a used book shop, maybe the owner has time to run back to check twenty reference books to research points.

But you are standing in the store, looking at the book, and you’re not sure, you’re on your own. If you’re specialized, you’ve got a better chance of coming up with the right answer. This is not to say you should never go out of your field; but in your field, go for depth. Learn everything you can. If you’re a science fiction fan, a modern lit fan, a devotee of travels and voyages, there are specialized bibliographies and reference books you can use to track down and discover new points.If you’re interested in children’s books, study the authors, and pay attention to every detail of the book in your hand.

We’ eve looked at the details of the edition; now it’s time to look at the details of condition. You can own a copy of the rarest book in the world, and if the boards are off, the hinges sprung, if there’s writing and foxing on the pages and heavy water damage along the edges, all you got is a lump of worthless paper. For a first edition book to be collectible, there is nothing that affects the price as much as condition. Even the rarest first, if trashed, is just trash, not a collectible book.

It is the condition of the dust jacket that determines the largest percentage of the book’s price—-some dealers estimate as much as 80%—-and so this is where you should start grading. A wonderful book without a dust cover is just a reading copy. Collectors want prime dust jackets. That’s what they see first, that’s what’s displayed on the shelf, so the dust jacket should be treated like cash money.

When grading a book, look at the dust jacket first, and then move on to the book itself. When you look at catalogs, you’ll see most dealers will give one grade for the book itself, and another for the dust jacket. The whole package is important, but the dust jacket has priority. Without exception for books produced in the last 40 years, there is nothing more important for the book’s value than the dust jacket.